Why plant native trees?

The subject of native trees in the UK is an emotive topic. Many people want to plant only natives, and it's easy to understand why. There's no doubt that, in an ideal world, planting natives is a sound and wise choice. These trees gradually established after the last Ice Age when glaciers melted. They were present when the UK was still connected to mainland Europe, before the formation of the English Channel. Around 8,000 years ago, the 'land bridge' between Britain and France, known as Doggerland, was swept away by a tsunami, thus leaving Britain as an island. Over the centuries, a huge number of life forms created an association with the native trees, depending upon them for food and shelter. Generally speaking, native trees provide the greatest benefits for insects, birds, small mammals, reptiles and other wildlife. Some of the best in the UK include the humble holly, native hawthorn and of course, the mighty oak.

Not only does the planting and care of native species help to safeguard the longevity of the trees themselves, but also the plant, fungi, insect, animal and every other species that depend on them. Not to mention the important aspect of a sense of belonging or spirit of the place, sometimes known as the genius loci. It is, however, important to acknowledge that the Earth continues to warm and ice is still melting and retreating. Everything on this planet is constantly evolving and species continue to recolonise the once frozen land. The subject of native trees is therefore not static.

You might assume that London plane trees are natives. However, this species (above) only arrived in the UK in the 16th or 17th century. The exact history of its origin is unkown. It is thought that Platanus hispanica's parents were the oriental plane and American plane - from different continents on the opposite sides of the world! Some believe that the two species hybridised naturally in Spain and the offspring were brought to England. Alternatively, others wonder if John Tradescant, an avid plant collector and botanist during the 17th century, purposefully crossed the two species in his London garden. Whatever the origin, the London Plane has been a huge success within the city because it is able to withstand pollution and it is long-lived. It provides valuable shade and shelter, it is both stately and elegant and helps to absorb and dissipate rainwater.

Constantly evolving

Indeed, we now have a considerable range of what we might call 'naturalised' species. These are those that colonised our land after the last ice age and after the English Channel was formed. They are now common in the landscape and some might regard them as being native. They include Aesculus hippocastanum (horse chestnut), Juglans regia (common walnut), Larix decidua (European larch) and Quercus ilex (holm oak).

Whether native, naturalised or exotic, trees in general are our best allies in the climate change crisis and most people now realise that they are essential for so many different reasons. The most important factor to consider, is the suitability of the species to their local environment, taking into consideration the soil type, the space and the location.

Which trees are native to the UK?

The range of tree species that are considered to be native is surprisingly small. There are around 55 medium to large native trees, with additional small trees and large shrubs. They include:

Alnus glutinosa (Alder), a tree that is highly suitable for growing in wet soils and along riverbanks.

Acer campestre (field maple), a small tree with beautiful yellow leaves in autumn.

Betula pendula (silver birch), with its unmistakable white bark.

Betula pubescens (downy birch), happy to grow on acid, poor and wet soil.

Carpinus betulus (hornbeam), a highly versatile tree that can be grown as a hedge or allowed to grow into a gnarled and mighty full-sized specimen.

Corylus avellana (hazel), a tree that will grow on chalky soil, producing whippy rods suitable for weaving and even water-divining.

Crataegus monogyna (hawthorn), a small tree that has red berries. Can also be grown as a hedge.

Fagus sylvatica (beech), a stately tree that has smooth, grey bark that sometimes looks as if it has rippling muscles. Likes light soils and won't tolerate waterlogging. Sometimes known as the queen of British trees.

Fraxinus excelsior (ash), once one of the most common trees but sadly decimated by ash dieback disease.

Ilex aquifolium (holly), loved for its red berries in the middle of winter.

Juniperus communis (juniper), an evergreen conifer that has blue/black berry-like fleshy seeds used in gin-making.

Malus sylvestris (crab apple), with fruits that can be used to make crab apple jelly at the end of summer.

Pinus sylvestris (Scots pine), native to Scotland. An evergreen conifer that can live for hundreds of years. Our only native pine.

Populus tremula (Aspen), a charming tree known for its leaves that flutter in a breeze.

Populus nigra (black poplar), once common but now rarely seen, it is considered to be endangered. Likes river banks and floodplains. The timber was once used for cartwheels and floorboards.

Prunus padus (bird cherry). Covered in racemes of fragrant white blossom in late spring followed by glossy black berries, loved by birds.

Quercus robur (English oak). One of the UK's most iconic trees, it is sometimes called the 'ruling majesty of the woods'. It has been affected by disease in recent years including 'sudden oak death', 'oak decline' and pests such as the oak processionary moth.

Sorbus aucuparia (rowan), with attractive clusters of red berries and good autumn colour.

Sorbus torminalis (wild service tree), a tree with white spring flowers followed by edible fruit that were once known as chequers.

Salix alba (white willow), an elegant, spreading tree that is happy near water and in boggy ground. The leaves appear silvery white from a distance. the tree produces catkins in spring.

Salix caprea (goat willow), is often called pussy willow because of the soft catkins. Likes damp woodland, hedgerow and scrubland in addition to riverbanks and even coastal locations.

Taxus baccata (yew), beloved of Churchyards, this evergreen tree responds well to pruning and can be used for topiary and hedging as well as forming a large tree. Produces fleshy red berries.

Ulmus (elm). The English elm, Ulmus procera (foliage shown below), might only be native to the southern parts of the UK. Sadly, the trees are now rarely found as fully grown specimens as a result of Dutch Elm disease that has ravaged the species. There are, however, hedgerow shrub forms of elm still surviving.

Native trees versus naturalised

Naturally, there is strong support for native trees here in the UK. But it's important to remember that the pattern of native species associated with any particular place continues to change as the climate fluctuates. And now that the climate shift is so extreme, said to be greater than at any time recorded over history, it is vital to attempt to increase the tree canopy and extend the number of species that can thrive in the UK. We need to grow a tree population that is as resilient as possible to the effects of climate change together with the increased level of pests and diseases. It seems that native species alone will not be able to cope.

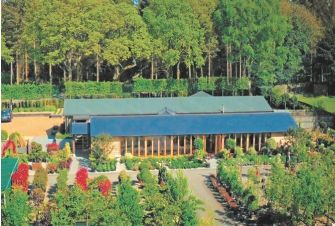

So, should we avoid planting non-native trees? Here at English Woodlands, we firmly believe that naturalised trees alongside natives are not only beneficial but vital in order to futureproof the biosecurity of the UK. We need the shade, shelter, wildlife habitats, water management, soil stabilisation, carbon capture and pollution control that is provided by all trees, not just natives. Furthermore, it's important to appreciate that our insects and wildlife can benefit from longer flowering and fruiting periods provided by non-native trees, as many provide flowers and fruit across different seasons.

Ensure to source plants from reputable nurseries that have been certified as 'Plant Healthy'. We need to prevent a raft of new diseases invading our wonderful trees within the UK - both native and naturalised!