Should we plant exotic trees?

The debate regarding native versus non-native trees in the UK is ongoing, and one that is unlikely to be resolved in the near future. There are those who feel strongly that we should try to preserve the heritage of our plant history by planting only natives. After all, they belong here and, by and large, they provide the greatest habitats for wildlife and offer the highest biodiversity benefits.

But others are certain that we now need to think and plan for the future by mixing exotics with natives. They believe it's no longer possible to restrict our planting because there are not enough robust native species to choose from. They cite climate change as an important factor for consideration. Some native plants are finding it difficult to thrive within challenging conditions. Also pests and diseases that have already been imported, are decimating many of the natives.

There is no right or wrong opinion because most views are perfectly valid. Keeping an open mind is probably the best course. The planet is evolving and we need to adopt flexible thinking to keep pace with a constantly changing world. The story of evolution is not new - however, the warnings of a pathway towards the sixth mass extinction is certainly not to be ignored. Nor is the fact that Earth is said to have lost at least half of its wildlife over the past 40 years, according to WWF (World Wide Fund for Nature).

So how can we help to protect our planet?

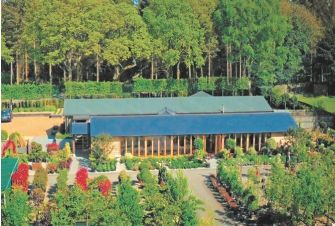

Whilst recognising that the big picture can seem too vast to contemplate, it's important to acknowledge that every single person can do something. Just one window box filled with plants can make a difference by providing nectar for insects. One shrub within a concrete yard can support life for hundreds of creatures. One tree planted today can turn into a magnificent emblem of hope for the future. The Magnolias growing adjacent to magnificent architecture below are undoubtedly beautiful, but they are not native.

Native versus non-native: points to consider

Which tree is best? Native or non-native - in other words, are exotic species as good as the UK's own? The argument extends to all plants, not just trees.

- Firstly, it is vital to source plants from reputable UK nurseries that have been certified as 'Plant Healthy'. We need to prevent a raft of new diseases affecting even more of our UK stock.

- Secondly, it's useful to recognise that pollinators including bees and butterflies benefit greatly from longer flowering periods. Many non-native plants flower across different seasons, thus extending the flowering period that is offered by native plants in the UK. There are many thousands of 'plants for pollinators' if you take into consideration the more exotic species and some of the larger exotic flowers carry heavy loads of nectar. This is not to ignore the fact that some insects feed exlusively from a specific type of plant. The Brimstone butterfly, for example, has larvae that need buckthorn or alder buckthorn - nothing else will do. The hazel dormouse lives in deciduous woodlands, hedgerows and scrub and relies heavily on hazel trees for its existence. We should never neglect our natives in favour of exotics.

- It's interesting to contemplate how native species originally arrived in Britain. It happened very gradually after the last Ice Age some 11,000 or so years ago. The ice destroyed most previous vegetation and much of the soil, but left a blank canvas ready for new colonisation by plants. The list of native species is still remarkably small, not only for plants but animals too. It's fair to say that the collection of truly British flora and fauna is impoverished. It also becomes clear that there is no absolute distinction between native and non-native species. Some that arrived after the ice age are classed as 'near natives' as they arrived from neighbouring Europe. Others have gradually moved in from further afield, sometimes described as 'alien' or 'exotic'. The definition of native, according to the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland is, 'either a plant that arrived naturally in Britain and Ireland since the end of the last glaciation (i.e. without the assistance of humans) or one that was already present (i.e. it persisted during the last Ice Age)'.

- Recent studies suggest that more than 70% of plants within a domestic garden are, in fact, non-native. But, because of the range of plant diversity, they tend to support a wide range of wildlife. A 'monoculture' of very few plants, however, supports far less life, even if the plants are native. This could be true of a closely-cropped lawn with very little planting around the garden. Or an immaculately designed space with a limited palette of plants. The benefits of allowing grass to grow longer changes the balance in a positive respect because other species naturally colonise within . Swapping grass for artificial turf swings the pendulum firmly to negative.

- One of the most important tasks for anyone looking after a garden or outdoor space, is to keep a check on plants that become invasive. It could be a native bramble that chokes every other plant nearby, or an exotic Japanese knotweed - which is probably the most invasive species in Britain. Most things, in moderation, are acceptable and each plant will offer something in terms of biodiversity and wildlife benefits. This includes 'weeds' including dandelions, daisies, buttercups, vetch, clover and many more familiar plants.

- The same goes for trees. Our British native selection includes species such as Alder, Ash, Beech, Birch, Blackthorn, Box, Buckthorn, Crab Apple, Dogwood, Elder, Elm, Field Maple, Hawthorn, Hazel, Holly, Hornbeam, Juniper, Lime, Oak, Pear, Poplar, Rowan, Scots Pine, Wild Cherry, Wild Service tree, Yew and more. But are all these truly native? Take beech, for example, Fagus sylvatica. It is actually only said to be native to the south east of Britain and south east Wales, although it now appears over a wider area. It is considered to be a 'later colonist' after the ice age. The wild apple, Malus sylvestris, is the native crab apple. It is widely believed that the apples we know today are direct descendents of wild apples that evolved in Kazakhstan. The Malus genus has been traced back 12 million years ago to China and these are thought to have been some of the first flowering plants on the planet. They led to the cultivation of other fruit trees including pears and plums. We have the Romans to thank for many early cultivations of apple varieties in Britian.

Are some trees weeds?

There are several tree species such as native birch and pine that are termed 'pioneer species'. They move in quickly and can establish themselves in disturbed soils and in environments that other trees might find challenging. Initially, they create their own immature 'forest', but eventually they modify the environment and other species find it easier to move in. This is the natural progression, or biological succession. But to a garden-owner or land manager, these trees with a high seed germination rate might be considered 'weeds'. It's all about man wanting or needing to control the environment in favour of those plants that are considered to be of higher value - and often the removal of so called 'weed trees' is necessary.

We are all caretakers of this planet and need to ensure that we do care about what we do to it. If our actions result from an informed viewpoint, the question of natives in favour of non-natives, or vice-versa, becomes less of an emotive issue.

Happy planting - enjoy caring for trees! You can browse the range offered by English Woodlands HERE